An introduction to Barolo is not exactly necessary. If you haven’t had a bottle or two, got some in your cellar or engaged in a debate on its merits vis-à-vis its reputation (and relative pricing), then what have you been doing as a responsible, wine-drinking adult? But at the same time, Barolo is one of those topics that demands as much attention as commitment to drinking it.

The repute of Barolo as one of Italy’s finest appellations can be traced back to 1840 when the House of Savoy instigated the production of Barolo as a dry style, spurred by apparent similarities between the indigenous grape of Nebbiolo to Pinot Noir. This initiative was with good reason, and the wine quickly gained traction amongst the Italian nobility as the wine de rigueur. This accolade stuck and was consolidated by DOC status awarded in 1966 and DOCG in 1980.

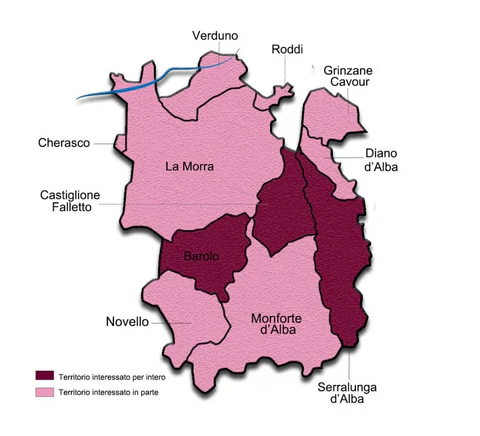

"Today, the appellation extends across 11 communes including Barolo, La Morra, Serralunga d’Alba and Monforte d’Alba. And despite extending over just 1,700 hectares, fierce debate surrounds prime plots"

The 11 Communes in Barolo

This comes as no surprise. Without resorting to that obvious pitfall of calling Barolo Italy’s counterpart to Burgundian Pinot Noir (because honestly that has been done to death), the terroir in this area displays such variety between, and within, the respective Communes that directly come to bear on the resultant wines. A trip into the hills of Barolo confirms this, even on the foggiest of days. The hills undulate steeply, with vines moulded into the curves of the landscape like a concertina. Add to this the presence of two soil types – Helvetian sandstone clay and Tortonian sandy marl – and you have optimum conditions for wines that truly have a sense of place.

Barolo Vineyards

In turn, Nebbiolo is a grape entirely tied to the heritage of Barolo. Indigenous to the region surrounding Alba, it has adapted over the centuries to the region and the challenges that it present. Its name stems from ‘nebbia’ that could either refer to the fog that collects in the surrounding valleys or the white bloom that forms on the grapes when they are ripe for harvest.

In turn, Nebbiolo is a variety notoriously difficult to nurture and really only flourishes in Piedmont (something that distinguishes it from the chameleon that is Pinot Noir). Budding early in the season, it is vulnerable to late frost and equally often does not reach optimum ripeness until mid-October and so only planted on south and south-west plots. Add to this its sensitivity to climatic fluctuations; a delicate balance between sunlight, warmth combined with a tendency to expend energy on profuse vine spurts. The result? A wine in which the vicissitudes of each vintage are paramount.

This context is all well and good. But the topic at hand is something else. Traditionalist versus Modernist approaches to Barolo. Where paths diverge.

And set the scene for a conflict that started in the 1980s with reverberations continuing to the present day. The Barolo Wars. This now historic contention saw producers in the area divided into two camps. The Traditionalists and the Modernists, both with very different approaches to wine production. And over time their disagreements came to entirely reshape wider perceptions of Barolo, creating a fame and infamy that has given Barolo the status it has today.

The lynchpin was the ageing vessel. The traditional choice has consistently been Slavonian oak, imported from the north-east of Croatia specifically on account of its tight grain which lends itself well to the large barrels known as botti. Because of the high tannins and acidity that typifies Nebbiolo, the upheld perspective is that maceration should take place for between to 15 to 30 days followed by long ageing in barrels between 5,000 to 10,oo litres to create a balance between these aspects. And of course, they are right; these wines have the potential to keep for decades, over which time the tannins mellow, the acidity drops and those prized notes of leather and undergrowth come to the fore. Anyone who has had a good bottle of 1978 Barolo knows that this tried and tested method pays dividends.

The downside? Wines that, as perfect as they can be, require years fining in barrel followed by even longer in bottle before those tannins have softened. It took social, and indeed political upheavals to instigate a different approach. Recognition of an increasing taste for lighter, more fruit-forward wines set the cogs in motion for a revolution on (let’s face it) a miniature scale. And like many a revolution, time was of the essence. Shorter maceration, shorter fermentation and shorter ageing. The means to do the latter came down to that old refrain that size really does matter. In a method first implemented by Angelo Gaja in Barbaresco,, French oak barriques of 225 litres were the gateway drug to creating a Barolo that did not require years of ageing to acquire oaky notes due to the greater wine to oak surface ratio smaller vessels engender. Complement this with less intense tannins and a more fruit driven profile that appealed to more International tastes.

A win-win for the battle of Modernists against Traditionalists then. Not so. Have you ever heard of a revolution where the opposition goes quietly. Didn’t think so. Plus in the world of wine, the boundary lines are always going to get a little hazy. Retaliation was swift. Upholders of Tradition were swift to venture that ‘faster, quicker’ flew in the face of time-honed techniques and obscured the very characteristics of Nebbiolo that define Barolo.

Moreover, acceptance of these wines as Barolo DOCG was an affront to those who had the wherewithal to uphold the criteria than define the appellation.

But a drawn out battle eventually becomes irksome. Because at the end of the day, the primary goal here is, and always will be, to create exceptional wines that express the characteristics of Nebbiolo and Barolo, not to mention the choices of each winemaker. Over time, there has been a recognition of the merits of each approach and a recognition that the distinctions do not need to be so hard and fast. Add to this an innate (if subtle) desire to rebel against the methods of your ancestors and there is endless potential for variety.

There are instances such as E. Molino where there is a dedication to Modernist approaches despite the planting of the first vines in 1973, when the tried and trusted method was very much The Only Way. Under Sergio Molino there has been a move to barrique, as in the Riserva del Fico that is aged for 24 months in French barriques and the Bricco Rocca that is aged in barrique for 18 months in barriques. But this decision is not the only factor that comes to play on the wines; with emphasis also placed on the minutiae such as separate vinification within the same vineyard to extract the finest elements from each bunch.

The same can be said of Conterno Fantino. Established in 1982, Claudio Conterno and Guido Fantino firmly aligned themselves with the Modernist movement. The use solely French oak barrels but caveat this with the fact that they choose the size of the barrel according to ‘the vineyard, vintage and other variables’, in order to innovate. The benefits of this are particularly apparent given the commitment to making single vineyard wines such as the Sori and the Vigna del Gris.

At Cascina Disa, Elio Sandri continues the Traditional methods implemented by his father Giovanni Sandri. This means ageing in Slavonian oak barrels for over five years followed by two years ageing in bottle prior to release. Drinking his Barolo Perno, a wine of intensity and unbridled elegance, there can be little debate that the Traditional method pays dividends to those who are committed to it. The same can be said of Pietro Benevelli, where Massimo Benevelli continues the Traditional approach of ageing in botti implemented when the estate was established in 1978.

Luca and Elio Sadri in the winery tasting Barolo

Umberto Fracassi similarly follows a Traditional approach perhaps aligning with the political affiliations of the founder, Senator Domenico Fracassi. For their Barolo ‘Manteotto’, the wine is aged in a combination of Slavonian, Aller and Never oak for 4 years.

This in turn sets the tone for producers who deploy both methods and demonstrate the strengths of each.

Eraldo Viberti for instance uses both Traditional and Modern methods: his Roncaglie is aged in botti and the Rocchettevino in barrique.

Complement this multitude of approaches with the work of newcomers such as Cristina Prandi. Her family’s commitment to Barolo extends to the 1860s but she refuses to let the weight of the past suffocate a myriad of knowledge. Her Barolo of 2021 will age until 2025 so the results are forthcoming, but with a combination of cement for maceration and a blend between botti and steel tank for ageing, there is a clear drive to shake off preconceptions of rigid determinations.

This might, therefore, be a conversation about Barolo Wars. But what comes out in the end is simply the brilliance of Barolo.